Christiana awakened as the sun rose over her little cabin in Missouri. The heavy woods surrounding her home shrouded the sun for much of the day. At times the quiet of the woods made her lonely. She thought back to her days when she lived in Tom’s Brook, Virginia. Christiana missed the view of the Shenandoah Mountains in the distance. The faint green of trees on the mountains in the Spring foretold new life for the earth and the creatures living upon it. The colorful red and gold of the trees in the fall spoke of winter to come. She yearned for the simpler days when John Ridenhour, her husband, wooed and eventually married her.

Christiana and John lived with her parents, Henry and Mary Catherine (Hiatt), on land next to the Great Wagon Road in Tom’s Brook, Virginia. The road began at the Port of Philadelphia and terminated in Augusta, Georgia.¹ It was one of the most important colonial routes, traveled by the German Palatines and Scots-Irish immigrants looking for greener pastures. Each day clouds of dust and the clang of metal meeting rock arose on the road as wagons loaded with people, furniture, and goods rumble by while the Zumwalt’s and Ridenhour watched.

The corn husks in her mattress rustled as Christiana arose from her bed. She shivered and dressed quickly. The cabin was cold. Soon she would have to break the ice-covered creek for drinking water when winter settled upon the land. She remembered when her father announced he would follow his brothers to Lexington in Fayette County, Kentucky. John decided to move their family and head west with the others. The draw of lands unknown was too hard for John to resist. Christiana thought it was unfortunate that women didn’t have much say in these life-changing decisions. Once they left Tom’s Brook, she would miss her friends and neighbors. Christiana would never hear the bubbling sound or taste the cold, clear waters of Tom’s Brook. Tears sprang into her eyes as she remembered watching the sun climb out from behind the shadow of the Shenandoah Mountains as the family left the only land she ever knew.

In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail from Fort Chiswell, Virginia to the Cumberland Gap in Kentucky. The narrow path, though steep and rough and could only be traversed on foot or horseback, opened Kentucky to those seeking new land.² The Zumwalt’s, like other pioneers, traveled in flatboats down the Ohio River to various destinations in northern Kentucky.³ As the Revolutionary War ended in 1781, the Zumwalt brothers, Adam, Jacob, and Christopher, arrived in the Lexington, Kentucky area in December of that year.⁴ It was a time of upheaval. A year before their arrival, Ruddle’s Station, about forty-one miles from Lexington, was in turmoil. A raiding party of Indians and British soldiers killed several settlers in the area. The remaining settlers were captured and force-marched to Detroit.⁵ John and Christiana missed the worst of the fighting arriving sometime in the mid-to-late 1780s.

Christiana quickly put logs in the fireplace to warm the cabin; the glow from the crackling fire warmed her. She put the coffee on the fire to boil and breakfast in a pan to cook. She reminisced about her time in Kentucky as she made breakfast. The undulating hills of Kentucky were beautiful and offered abundant water; the valleys were fertile and game teemed in abundance. However, she never felt at ease while in Kentucky. The stories of the battles between the settlers and Native Americans in the recent past unsettled her. It seemed the men in her family were rolling stones, always looking for a better place to live and never giving thought to how it affected the women in their families. Christiana sensed the men were getting restless. While she resented having no say in her future, she was relieved when she learned her father, uncles, and John purchased tracts of land from the Spanish Government in the Missouri Territory. They were moving west of the quickly growing village of St. Louis. She was hopeful the growing population would insulate them from problems with the Native Americans.

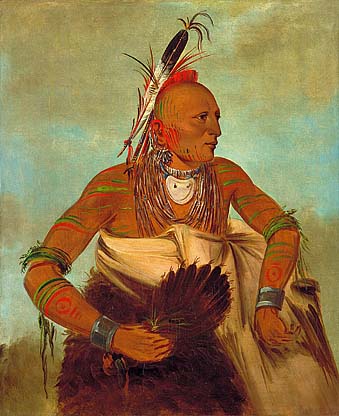

John Ridenhour purchased two tracts of land from the Spanish government in 1799; the first was north of the Missouri River on Peruque Creek and sold to Michael Crow. The second was 450 arpens on the Missouri River in the district of St. Andrès.⁶ Christiana was mistaken if she thought she would have little interaction with Native Americans. The Osage Indians lived about two hundred miles up the Osage River from where it emptied into the Missouri River. Christiana may not have known the land purchased by John was in the Osage hunting grounds. The Osage Indians hunted over a large area of land between the Missouri River on the north, the Mississippi River to the east, and the Arkansas River to the south. To the west, on the plains, they hunted buffalo.⁷ Osage warriors were impressive in stature. George Catlin, the famous painter of tribal groups in the 1830s, described them as “the tallest race of men in North America, either of red or white skins.” Various chroniclers and eyewitnesses have stated that few Osage stood less than 6 feet in height, while many reached a well-proportioned 6½ or 7 feet tall.⁸ The plains Indians prized horses. Horses were fair game if stolen from other Indian tribes or the white man.

The coffee smelled good. She hoped her supply would last through the winter. Christiana poured some and tried not to think back to when John died in 1803. She remembered they were in the habit of letting their cows and horses graze in the forest. On that fateful day, while rounding up their horses and tying them together, they stopped to water the horses at the creek that ran through their property. She felt their presence before she saw the looming shadows of the mounted Osage Indians approaching them. They were imposing. Suddenly they began yelling and demanded John give them the horses. It happened so quickly. John turned his horse and yelled for her to go; he and the horses would follow. Then came the sound of the blast from a gun. Turning, she saw John on the ground; blood was oozing from under him. As she jumped off her horse, she slapped him to make him run; he took off with the other horses following him. An Indian hit her with his rein when she ran toward John to see how he was; he was angry the horses had gotten away. She will never know why they left her standing and rode away on their horses.

As she cleaned her breakfast dishes, she was thankful to be alive. It was an ordeal to get John’s body back to the cabin, alert her relatives, and bury him. Her children were heart-broker. Her step-children, Mary and Henry, were a great help to her. Bernard and Betsy had been old enough to feel the loss of their father. She was sorry that Jacob and John didn’t remember anything of their father as the years went by.⁹ After the attack on Christiana and John, several of her neighbors left the area, fearing that they too would be visited by the Indians. She had nightmares for many months after the attack. However, Christiana was proud that she had stayed on her land after John’s death. She wasn’t going to get anyone scare her away.

Christiana was a young woman when John died. She was also recovering from the loss of her young son Daniel who died a few years earlier. She was left a single widow of thirty-six with five fatherless children to raise. Fortunately, she had enough money on which to live. However, she was alone and living in an area of the U.S. where French, Spanish, and English cultures often clashed with each other. And worse, she lived in a world dominated by men. Christiana had to learn how to navigate this world that was so alien to her.

Toward the end of 1803, when John died, the Spanish conveyed their colonial lands and administration to France in November. Then in December, the French sold this land, known as the Louisiana Purchase, to the United States. ¹⁰ These actions created turmoil when people had to prove the validity of their Spanish and French land grants to the United States government. Before the land grants could be approved, they needed translation from French or Spanish into English. People had to present their paperwork and provide depositions before the Board of Land Commissioners hoping their actions were enough to prove their ownership.¹¹ The process took many years to resolve the land ownership of hundreds, if not thousands of people. Christiana, and many of her relatives, were lost in limbo while they waited to hear if they could stay on their land.

As the sun set in the west, leaving a beautiful orange and purple glow to the sky, Christiana remembered how stressful it was to provide the deposition to the Board of Land Commissioners in 1807. She had pushed the painful memories of that dreadful day when John died deep into her soul. It was hard. Sitting through the deposition dragged those memories inch by inch from deep within her. Losing John was hard, but she persisted. Christiana was proud of herself. By herself, she had successfully raised her children and taken care of herself for many years.

In the deepening evening, she smiled to herself. She smiled because she had received good news. Her heart burst with joy and pride when she heard her claim was approved.¹² Fifteen years later, at the age of 55, she was now the proud owner of 450 arpens of land.

John Ridenhour and Christiana (Zumwalt) are my fourth-great-grandparents. It’s no wonder John and Christiana’s father, Henry, was a rolling stone. Both had ancestors that came to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from Alsace, France, in 1737¹³ and 1738¹⁴. Christiana’s uncle Jacob Zumwalt is remembered through time for building Fort Zumwalt, one of the first forts in the Missouri Territory.

Several books have captured the true story of John Ridenhour’s death at the hands of the Osage Indians. One such book told of John’s death and the escape of his unnamed wife. ¹⁵ Like millions of pioneer women in the U.S., whose names are lost, so was Christiana’s. She, like many women, endured hardships as they traveled the roads of the wilderness, often pregnant and taking care of the needs of her husband and children. They were the true backbone of our nation as it grew and expanded to the west. They had little to say in the decision-making for the family, yet they were strong and resilient like Christiana. It was only through delving into the records that Christiana’s name and story came to light. One can’t know what Christiana thought or felt. Hopefully, through her fictionalized thoughts in these writings, the world will know her name, her story, and how strong she was.

As a side note, the creek that ran through John’s property was called Ridenhour Creek for many years. Today it is called Fiddle Creek. When I was a child, I went to Girl Scout Camp, known as Camp Fiddlecreek. I didn’t know my connection until I began researching my Ridenhour ancestors.

¹The Great Wagon Road, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wagon_Road

²The Wilderness Road, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilderness_Road#:~:text=In%201775%2C%20Daniel%20Boone%20blazed,only%20on%20foot%20or%20horseback.

³The Rivers of Northern Kentucky, https://www.nkyviews.com/Other/misc_rivers.htm

⁴Sherry Sharp, Moyer/Snyder Family, Our Family History

(http://sherrysharp.com/genealogy/getperson.php?personID=I10592&tree=Roots : accessed 25 Jul 2018), Record for Adam, Jacob, and Stoffel [Christopher] Zumwalt.

⁵Ruddles Station Kentucky, https://www.frontierfolk.org/ruddles.htm

⁶Land Record for John Ridenhour, Book C, P. 195, 7 Dec 1799; Commissioner’s Certificates, U.S. Recorder of Land Titles; digital images, Missouri State Archives, “1st Board of Land Commissioners, U.S. Recorder of Land Titles,” Missouri Digital Heritage (https://s1.sos.mo.gov/records/archives : accessed 30 Aug 2017). Note: An arpen is a French unit of land equal to .85 acres.

⁷ The Tribes of Missouri, Part 1, https://missourilife.com/the-tribes-of-missouri-part-1-when-the-osage-missouria-reigned/

⁸Fort Scott National Historic Site, The Osage, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/osage.htm

⁹ Christiana Ridenhour claimed 500 arpens of land granted to John Ridenhour, 7 Dec 1799; Original Claimants -1st Board of Land Commissioners, U.S. Recorder of Land Titles; digital images, Missouri State Archives, “Citing Book C, Page 195,” Missouri Digital Heritage (https://s1.sos.mo.gov/records/archives : accessed 11 Sep 2017). The document named Henry, Mary, Betsy, John, Barnet, and Jacques, heirs of John Ridenhour.

¹⁰ The Louisiana Expansion, https://www.umsl.edu/continuinged/louisiana/Am_Indians/1-Osage/1-osage.html

¹¹Missouri Digital Heritage, French & Spanish Land Grants, https://www.sos.mo.gov/mdh/curriculum/africanamerican/guide/rg951#:~:text=At%20various%20times%20between%20the,to%20settlers%20in%20the%20area.

¹²Missouri, Record of Land Titles in Missouri 1804-1867, Land Grant approved for Christiana Ridenhour; Land Commissioner Minutes, H-5, item 161; St. Louis County Library, Special Collections.

¹³Archives.org database and images (http://www/internetarchive.org : accessed 27 Jul 2018); Listing for Andrew Sunwald; Citing “A collection of upwards of thirty thousand names of German, Swiss, Dutch, French and other immigrants in Pennsylvania from 1727-1776”, P. 107.

¹⁴Mona McCown and Nona Harwell, Reitenauer Immigrants, The Early years; PDF Download, Ridenhour Family Genealogy (http://webpages.charter.net/eridenour/ridenour.html : downloaded 11 Aug 2018), 133.

¹⁵Louis Houck, A history of Missouri from the earliest explorations and settlements until the admission of the state into the union. (Chicago, Illinois: R. R. Donnelly & Sons, 1908), II: 73.

I was so excited to read this entry as John and Christina are also my 4th great grandparents. My mother was a Ridenhour. Does that make us cousins? I have tried in vain to get copies of the Ridenhour Newsletter that was started many years ago and is no longer exists. Have you seen it or know how to get copies of it?

LikeLike

Hi Chris. I do believe we are cousins. Did your mother live in Osage or Gasconade County, MO?

I have heard of the newsletters but have not been able to find them. That information has been elusive. Most of my information came from the book “Reitenauer Immigrants, The Early Years.” I researched their sources to confirm they were correct before I used them in my stories. Good to hear from you. If you ever want to collaborate, contact me.

LikeLike

I understand you are descended from Martin Ridenhour and I am descended from his brother Reuben. My mother was born in Thayer, Mo. If I ever can find the newsletters I’ll share them with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And if I find the newsletter, I’ll share it with you. Do you have any pictures o Martin or any of his kids? I have a picture of Martin that someone sent to me but it is not very good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome story💖💖

LikeLike

Thanks, Heidi. I always appreciate your comments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a creative and well-written story, lovingly told. I enjoyed reading.

LikeLike

Thanks, Eilene. The story is a departure from what I normally write. I always appreciate feedback from you.

LikeLike

What a fantastic story, thank you for sharing it and making it such an interesting read! I have come across the Zumwalt name while researching my 4th great-grandfather’s War of 1812 service. A regimental captain in southwest OH.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Zumwalt’s were in northern Kentucky. Several were in the military. It’s very possible the ones you came across were one of the brothers of my Christiana’s father, Henry.

LikeLiked by 1 person